Join The Brad Pack on Patreon!

〰️

Join The Brad Pack on Patreon! 〰️

The Brad Pack is the modern-day magazine, a multimedia digital community on Patreon focused on the unsung heroes and untold stories of sports and entertainment in the pre-Internet age.

For less than the cost of a venti Starbucks per month, subscribe to The Brad Pack on Patreon for Six Pack bonus content, deleted scenes, and new baseball content.

They say to never meet your heroes. Brad Balukjian doesn’t listen.

See what wrestling icons and industry buffs are saying in these reviews!

Join The Brad Pack on Patreon for new material updated every week!

-

Exclusive material from The Six Pack, The Wax Pack, and more!

-

Baseball, pro wrestling, and stories of sports’ unsung heroes all organized into collections of regularly updated original content

-

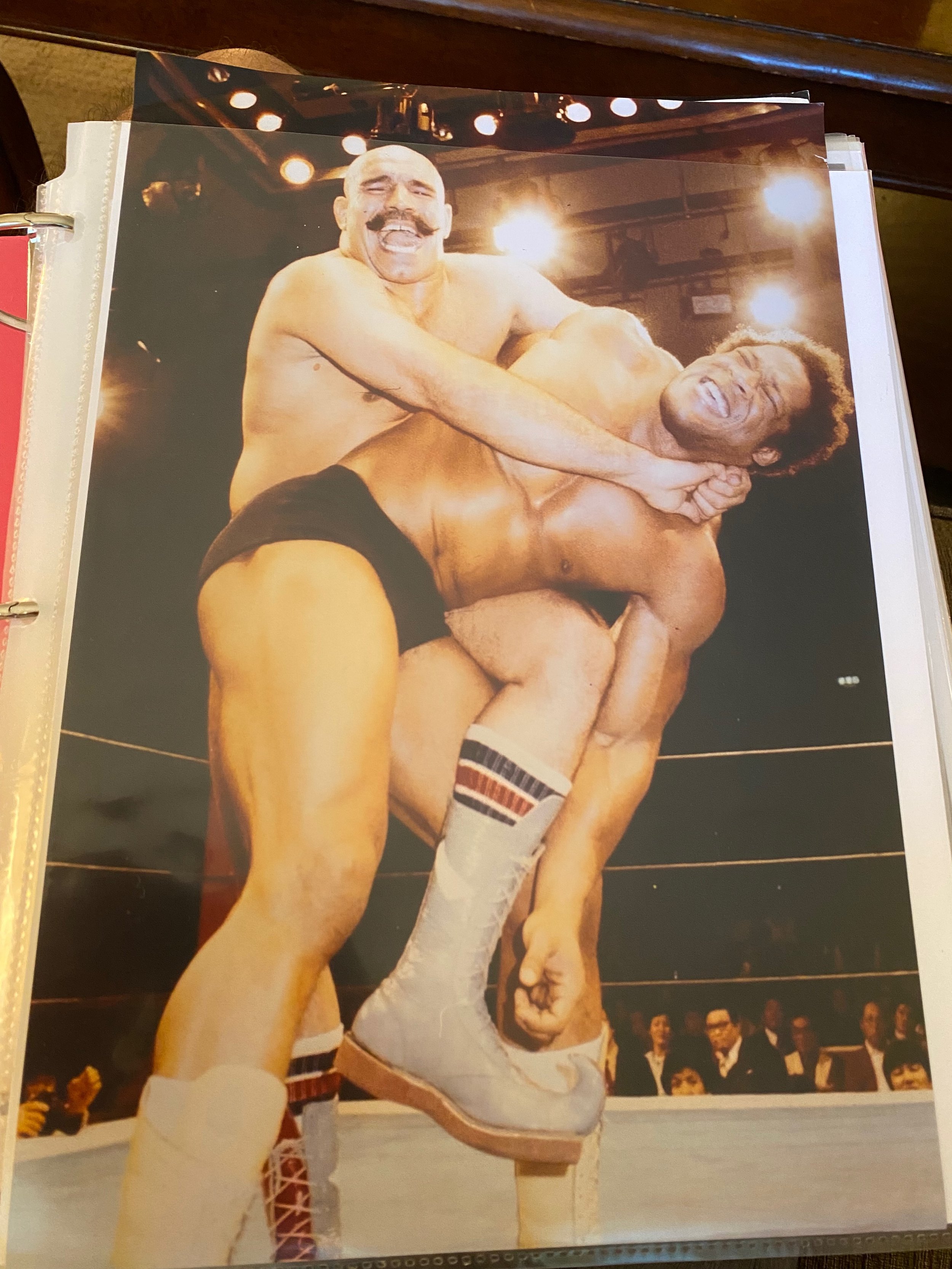

Images, copies of exclusive WWF documents, audio files, + more!

-

New interviews and content from the underdogs of baseball, sports, and entertainment's past.

Coming May 2024!

-

All-new longform magazine-style articles featuring an athlete or wrestler from the Brad Pack Era.